The words grimdark and noblebright arose as technical terms in the gaming world. There’s a certain amount of dispute about the exact definitions there, with a tendency to paint them in black and white terms (such as the slur that noblebright is all about rainbows and unicorns and flawless heroes).

In fiction, by contrast, especially adventure fiction (in which I class things like Westerns and Fantasy) they have come to be used to reflect two different and opposed styles of story. Since there is some dispute about the definitions, it behooves me to offer my own.

GRIMDARK

The notion that the actions of one person can do little to improve this world in decline, that the forces of evil and inertia and temptation will ensure that all of us are doomed. The best we can hope for is a little struggle with morally ambiguous heroes to oppose danger and maybe rescue for a brief time a few others.

NOBLEBRIGHT

The notion that the actions of one person can make a difference, that even if the person is flawed and opposed by strong forces, he can (and wants to) rise to heroic actions that, even if they may cost him his life, improve the lives of others.

Let me explain why I am firmly in the noblebright camp.

Why we tell stories

All human cultures tell stories around the campfire. Some are just for humor, of course, but the adventure stories tell of the efforts of people presented with problems and what happened, whether it’s the youngest son going off to seek his fortune, or the girl determined to free her swan brothers, or the boy who saves his village from flooding.

All human cultures tell stories around the campfire. Some are just for humor, of course, but the adventure stories tell of the efforts of people presented with problems and what happened, whether it’s the youngest son going off to seek his fortune, or the girl determined to free her swan brothers, or the boy who saves his village from flooding.

The sort of hero who is successful embodies the values of the culture, and his solutions to his difficulties illustrate the virtues needed, and the flaws to be overcome, in the character of a hero. No traditional tale glorifies the futile efforts to stand against overwhelming foes and just give up.

And for obvious reasons. Any culture that thinks “the good” is not worth fighting for doesn’t survive in a meta-Darwinian world where culture, too, is a survival of the fittest.

Traditional stories well understand the flawed nature of man, but that doesn’t stop them from valuing bravery, perseverance, kindness, generosity, and all the other virtues that make for moral men and women in their societies.

A moral hero may well die in the performance of his deeds, but more often his strategy is successful, and he reaps the benefits of his work directly. The story is an idealized guide for how a man should live and conduct himself.

Traditional tales are of course heightened stories: simplified from pure realism, illustrative of what is valued by the culture. Not many are about perfect characters who can do no wrong. After all, we’re talking about stories — where would be the interest in that?

Moral characters in fiction

In the end, we all die, nature and physics are indifferent, and the best of us is flawed. This is terrible knowledge, but useless as a moral guide. How can we live meaningfully, in spite of this? That’s what stories illustrate and suggest.

If we’re going to die anyway, surely it’s better to go down fighting?

A man fights, despite overpowering obstacles and probable doom, because he cannot be the man who doesn’t fight. As they say in Zulu, a hundred-odd men facing four thousand:

Pte. Thomas Cole: Why is it us? Why us?

Colour Sergeant Bourne: Because we’re here, lad. Nobody else. Just us.

And that’s just bravery. There are other virtues in our cultures — the generosity that shares one’s last meal with a beggar, the kindness that notices and helps the struggle of the weak, the conviction that it is better to save others than yourself, if the choice must be made.

Heroes don’t want to die, but they recognize there are more important things than personal survival, that the price of personal survival can be too high. Stories about heroes teach us these values, make them strategies for how we live our own lives — hardening us even in the teeth of an indifferent natural world.

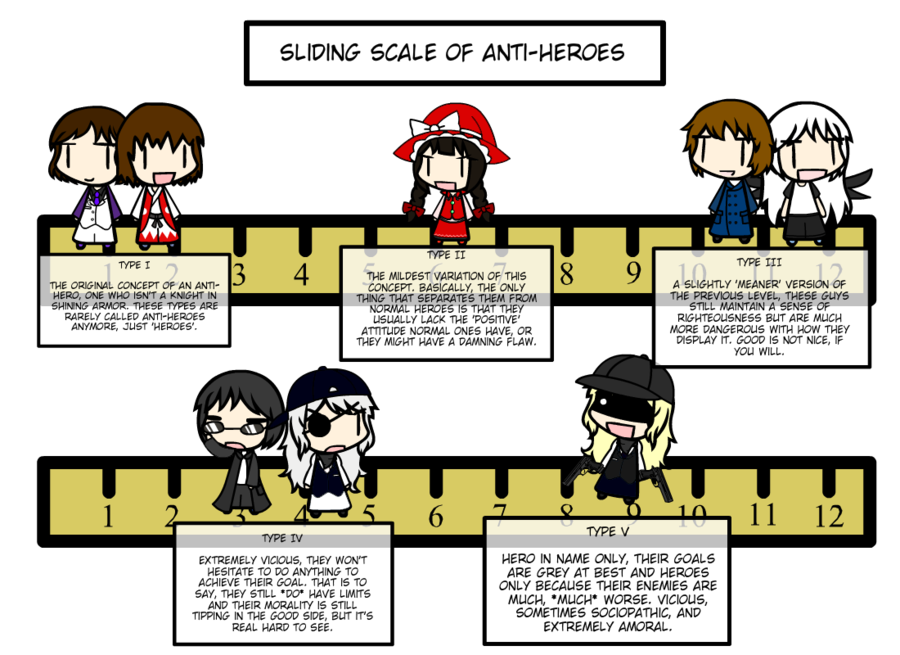

The rise of the anti-hero

The anti-hero concept rose most strongly in the early modern era with the Romantic movement. In fantasy, one of the startling archetype works was Stephen R Donaldson’s The Chonicles of Thomas Covenant, whose main character has no compunctions against rape when he thinks it isn’t real.

Anti-heroes are not nice people. They are self-interested to a degree not approved of in traditional cultures. If they do the right thing, it’s often for selfish motives. They tend to be untrustworthy, disagreeable, and vicious.

When an outlaw does a heroic deed, taking a break from his usual mayhem, which do we admire: the man or the heroic deed? Who would we rather spend time with? Who should our children look up to?

Grimdark stories call for anti-heroes, and some praise this because it is closer to reality, somehow — people really are deeply flawed, motives are truly mixed, not everyone can rise to the occasion. Ironic versions of traditional stories subvert their original teachings, and a style of “edginess” wins favor among those who wish to be labeled “cool.”

Does admiration for the anti-hero consist of a cultural value that should be endorsed? Or should his heroic deeds be admired despite his flaws, not because of them?

If you admire the flaws, you are dragging the hero down to your level, rather than elevating your goals to the virtues of a true hero. And yet, thinking heroically can still motivate people in the real world, as our ancestors knew, around their campfires.

Motivating characters vs motivating the protagonist

Why do grimdark stories leave me deeply unsatisfied? Partly because they collapse any distinctions between the types of characters that make up a story.

All characters need motivation (to be heroes in their own eyes), but not all can be protagonists of the story.

All characters need motivation (to be heroes in their own eyes), but not all can be protagonists of the story.

The protagonist in the story needs to stand against the opposing forces — without conflict, there is no story. The protagonist stands with us — we have to care about what actions he takes and what happens to him.

But the more immoral the protagonist, the less we want to identify with him, because he drags us down instead of raising us up. And the less difference there is between him and the villains (if the opposing forces are people). The worship of anti-heroes collapses that difference.

If there’s no difference, the story teaches us little and makes us despise everyone. We still make judgments — we can’t help it, it’s built into all of us. If no one in the story is worth our admiration, or serves as a guide to living, then what’s the point of the story?

This post originally appeared on Karen Myer’s blog here (reprinted with permission).

4 thoughts on “Grimdark vs. Noblebright”

I don’t know how I feel about these definitions being framed to talk about an individual. vs a collectivist action, after all I’m fairly certain Lord of The Rings fits into the HopeBright side of things easily but it’s very much a collective effort at the same time as it focuses on Frodo. Um besides that I found it interesting.